Camille Pissarro - the Father of Impressionism Part 2

Today we continue to look at the life of Camille Pissarro, his interactions with the other Impressionists, and the diversity of painting styles he achieved.

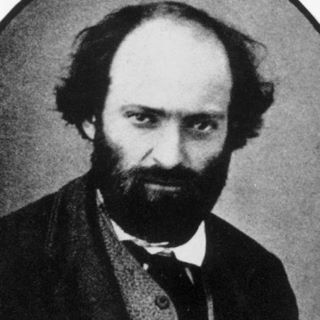

But first, the answer to the little puzzle at the end of Pissarro Part 1. Pissarro is on the left, and Monet is on the right. How did you go? Did you get it right? It is interesting that they could look so similar in some respects!

But now, back to Pissarro, who we left living in England, whilst the Franco-Prussian war of 1870 -71 was raging in France.

After the war, Pissarro returned to Pontoise to live, some 30 kilometres or so outside Paris. He then discovered that of the 1,500 paintings he had done over 20 years, (which he was forced to leave behind in Louveciennes when he moved to London), only 20 or so remained. The rest had been damaged or destroyed by the soldiers, and many used as doormats outside in the mud.

This was a huge loss in the record of the development of the Impressionistic style. Nevertheless, Pissarro set about replenishing his collection, and today there are at least 890 works still recorded.

Pissarro re-established his friendships with the other Impressionist artists of his earlier group, including Cézanne, Monet, Manet, Renoir, and Degas. Pissarro was very clear that he wanted to develop an alternative to the Salon and, in 1873, he helped establish a separate collective, called the "Société Anonyme des Artistes, Peintres, Sculpteurs et Graveurs," which included fifteen artists.

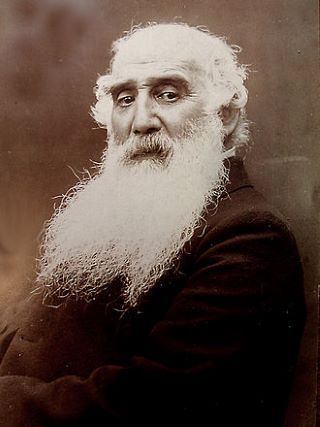

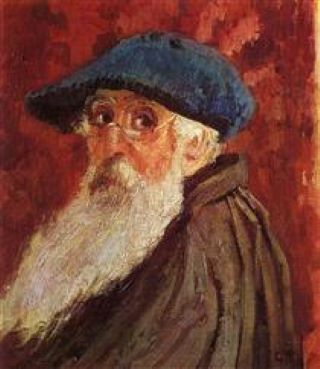

Pissarro created the group's first Charter of principles, and became the "pivotal" figure in establishing and holding the group together, despite the strong and varying personalities. With his prematurely grey beard, the then forty-three-year-old Pissarro was regarded as a "wise elder and father figure" by the group. Yet he was able to work alongside the other artists on equal terms due to his youthful temperament and creativity. One writer has said of him that "he has unchanging spiritual youth and the look of an ancestor who remained a young man.” 1

The following year, in 1874, the group held their first 'Impressionist' Exhibition, which shocked and "horrified" the critics. Nevertheless, Pissarro was committed to maintaining an alternative to The Salon. In fact, he was the only one who showed his work in all eight of the Impressionist’s Exhibitions.

He continued to foster the common objectives of this diverse, loose-knit group, even though the participants came and went. At one point, Renoir described Pissarro’s work as “revolutionary”. He was a mentor and a constant, unifying tie. Monet, Manet, Renoir, Degas, Gaughin, Caillebotte, Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt all joined the group at various times, but by 1879, Monet and Renoir had left, for various reasons.

Pissarro and Julie Vellay went on to have 7 children, but their daughter, Jeanne, died at age 9, just at the time Pissarro was involved in organising the First Impressionist Exhibition in 1874. This hit both Julie and Camille very hard as they were devoted parents.

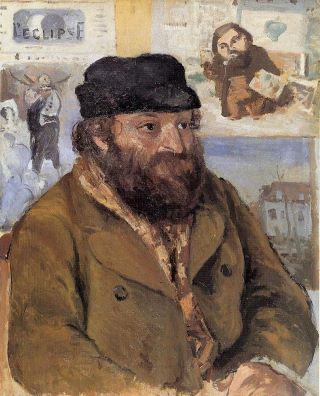

Pissarro also stood as a staunch friend to Paul Cezanne, who was a very tortured soul, mentally and emotionally. Pissarro’s quiet and considered ways were a calming influence on Cezanne. He listened to Pissarro’s advice and tuition when he would listen to no-one else. Cezanne in particular would stay with the Pissarros even when they moved further out to the countryside of Eragny.

In later years, Cézanne recalled this period and referred to Pissarro as "the first Impressionist". ‘We learned everything we do from Pissarro,’ said Paul Cézanne in the 1890s. ‘It’s he who was really the first Impressionist.’

In 1906, Cézanne, then 67, paid Pissarro a debt of gratitude by having himself listed in an exhibition catalogue as "Paul Cézanne, pupil of Pissarro."

Mary Cassat was a strong personality, but always liked the company of "the gentle Camille Pissarro", perhaps as a foil to her long, but tumultuous friendship with Degas. Pissarro was someone with whom she could speak frankly about the changing attitudes toward art. She once described him as a teacher "that could have taught the stones to draw correctly.”1

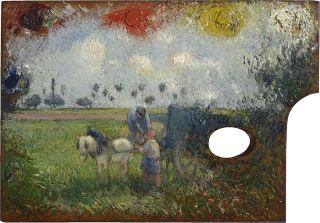

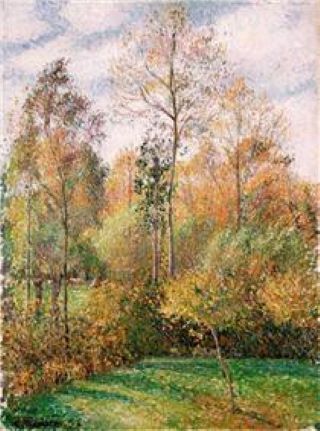

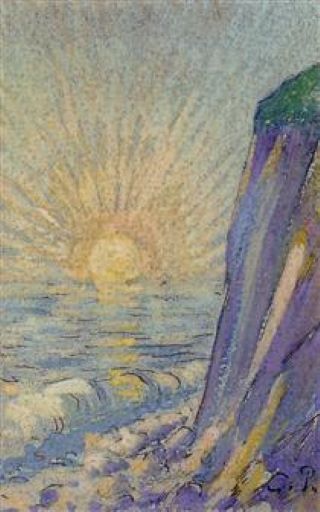

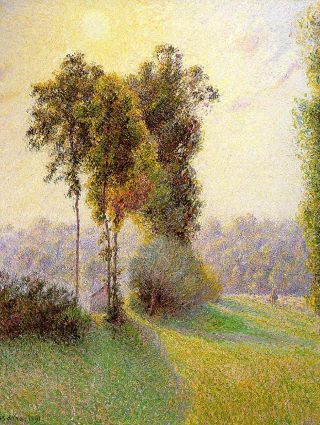

By the mid-1880s, Pissarro began to explore new themes and methods of painting to break out of what he felt was an artistic "mire". In 1885 he met Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, through his son Lucien, who was also an artist. Both Seurat and Signac relied on a more "scientific" theory of painting by using very small patches of pure colours to create the illusion of blended colours and shading when viewed from a distance. This style would later be named Neo-impressionism.1

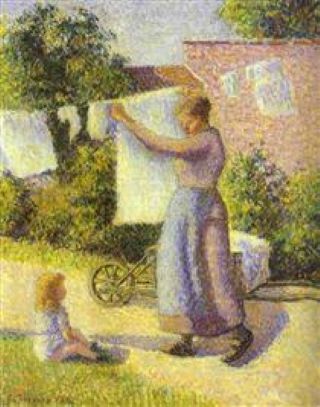

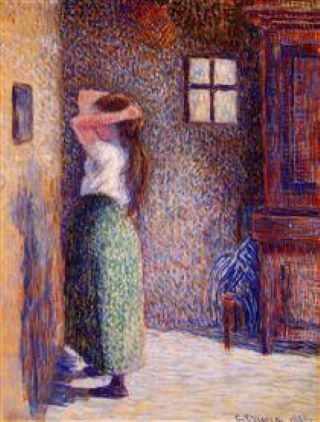

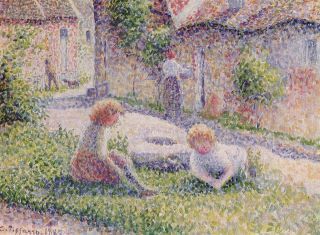

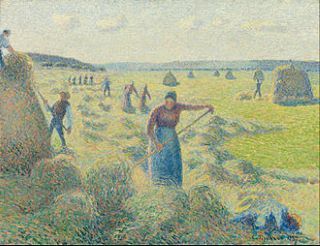

He toyed with this technique for a couple of years and then spent a couple more years experimenting with pointillism. This involved using small dots of pure colour, rather than small patches, and so was an even more time-consuming and laborious technique.

He exhibited with Seurat, Signac and his eldest son, Lucien Pissarro in this style in 1886, when Lucien was about 23. Can you see how these styles differ from the other Impressionists?

You could be forgiven for thinking that these paintings below were by Seurat, as he is very well known for this style! (We shall look at his life in a future post too).

Pissarro was also fascinated with Japanese printmaking, as were Monet, Cassat, Felix Bracquemond and Degas. He also worked with his son, Lucien, in this area. They worked together after the first Impressionist exhibition, as Degas owned a printing press. They even planned a monthly journal of prints, but this came to nothing when Degas and Caillebotte withdrew their support.

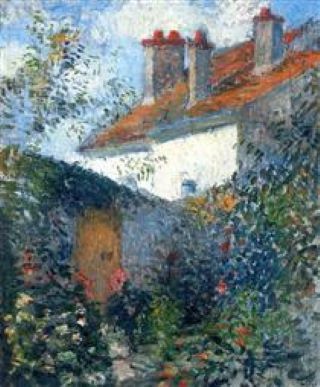

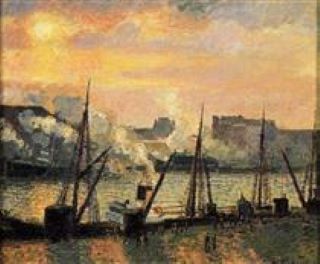

Later in life, Pissarro picked up the idea of a ‘series’ of paintings, from the multiple views in different lights that Monet had done of the cathedral at Rouen. The series of paintings of 'a Montmartre street' (below) was the result.

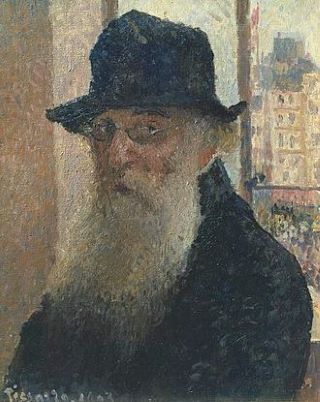

Camille Pissarro developed a persistent eye infection towards the end of his life, which stopped him being able to draw outdoors. The paintings from 1900 until his death in 1903 are almost exclusively views of outdoor scenes, done from rooms he hired in Paris, on the first or second floor, in order to get a better perspective.

Pissarro died of sepsis on 13 November, 1903, aged 73, and is buried at Le Pere Lachaise Cemetery, in Paris with his wife and other family members. I was fortunate to visit there in September 2019.

Three of Pissarro’s children also became artists – Lucien, Georges and Felix. Some of his grandchildren and great grandchildren also either became artists, or are involved in art.

It is a wonderful legacy of a man of quiet versatility and dedication.

If you would like to read more about Pissarro’s life and art, click here.

Footnotes

- Courtesy of Wikipedia